CENTRAL BANK DIGITAL CURRENCIES: HUMAN DATA-MINING GOES GLOBAL

By John Titus

Central bank digital currencies are being pushed as inevitably as Covid-19 injections. But why? As usual, the real reasons are not what official narrative would have you believe.

A. CBDC Background – What Is Happening and Why?

Currently, the monetary system features two tiers: a wholesale (and legally dominant) tier and a retail tier where all but a tiny handful of entities do their banking.1 In the wholesale tier, the issuer of money is the central bank. In the retail tier, commercial banks issue money. In both tiers, money is issued as debt, and therein lies the rub.

As proposed by the world’s central bankers, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) will partially collapse the two-tiered monetary system into a single tier in order to shore up a problem with the lower, retail tier (the one we use), but that will ultimately result in a system of total monetary control over the population by a handful of bankers. The switchover to a CBDC system, which will take several years to implement, represents a radical consolidation of power that dispenses with even the pretense of freedom and representative government.

Until very recently, central bankers had only indirect influence on the volume of electronic money (deposits) in the retail tier: by changing interest rates on electronic money in the wholesale tier, they could induce sympathetic changes in interest rates in the retail tier, which in turn would tend to increase (by lowering interest rates) or decrease (by increasing interest rates) the volume of money in the retail tier. When interest rates rise, people and businesses borrow less money, and when interest rates fall, they borrow more.

During the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008, central bankers ran out of rope as interest rates fell to zero, where they have remained ever since. Realistically, central banks cannot reduce interest rates to below zero without risking political upheaval. While this isn’t too much of a problem during “normal” times, at least as central bankers would have it, the inability to reduce interest rates further presents a very big problem should another big crisis hit. Of course, another big crisis did hit with the arrival of the pandemic in early 2020.

Central bankers had planned for that day, as it turned out. In August 2020, BlackRock presented a crisis plan of sorts to the central bankers of the world. BlackRock’s plan, entitled “Dealing with the Next Downturn,” proposed “going direct”—finding a way to inject money directly into the retail monetary tier, an “unprecedented” policy response.2

From the central bankers’ point of view, “going direct” represents only a partial solution to the vanishing runway problem. As implemented, “going direct” injects money into the retail tier only at its highest levels, by allowing the wealthiest members of the retail tier to sell their low-yielding assets (bonds) to the central bankers in exchange for retail electronic money that can be invested into high-yielding assets like the stock market.

This aspect of “going direct” has the very obvious tendency of drastically increasing inequality by making the ultra-rich even richer.

To solve this “problem,” central bankers are now proposing CBDCs as the solution. With CBDCs, central bankers would be able to issue money directly to everyone in the retail tier, though this “solution” is being pitched as a philanthropic effort to help “the unbanked” (that is, issuing CBDC to members of the retail tier who are so poor that they don’t have access to electronic bank accounts).

Of course, this will give central bankers the means to directly control every single transaction proposed to be undertaken with CBDC, a fact about which they have been quite candid.

That, in a nutshell, is the official CBDC story, though like anything else coming from central banking quarters, it is to be regarded with extreme suspicion, as it is virtually certain to have omitted a rash of material information. And indeed, that is the case with the nightmare that is CBDC.

This report will proceed as follows. Section B will describe the current monetary order, while Section C will explain the current monetary problem with the system. Section D will describe the CBDC “solution” proposed by central bankers but will also discuss two key downsides with CBDCs, one at the personal level and another at the civic level. Section E will describe how CBDCs are likely to be implemented and attempt to describe how the CBDC governance system might work. Section F will outline how CBDCs could very well lead to the loss of national sovereignty. Finally, Section G will offer suggestions on how to resist the totalitarian push by central bankers.

To be clear at the outset, this discussion is framed in terms of the U.S and its central bank, the Federal Reserve. However, as virtually all economies work on the same debt-based model, they all feature the same basic structure, as we shall see. For this reason, the discussion here, though nominally concerning the U.S. and the Federal Reserve, applies with equal force to nearly all of the advanced nations and their central banks worldwide.

B. The Current Monetary Order

The U.S. monetary system comprises four types of money and three classes of money issuers. For purposes of completeness, all are described here, though only two types of money and two classes of money issuers are of concern insofar as CBDC is concerned.

1. Types of money in our monetary system

The types of money in the U.S. system are as follows:

a. Cash: Cash (Federal Reserve notes) is created out of thin air by the Federal Reserve, which instructs the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in the U.S. Treasury on amounts and denominations to be printed based on demand. Cash is physical and for this reason would not seem to be of any concern insofar as CBDC is concerned. However, the monetary powers that be have repeatedly and explicitly stated that “cash is the model for CBDC design.”3 As central bankers would have it, CBDC is simply digital cash. There are reasons to be skeptical of this claim, however, as we shall see.

b. Coins: Coins are minted by the U.S. Treasury based on demand from banks and from retail orders placed, for example, by individuals online or by phone. Coins are physical and do not concern us insofar as CBDC is concerned except by way of reference. Additionally, the U.S. Treasury does not concern us at all because it is in no way involved with CBDC.

c. Bank money: Bank money is electronic (or digital) and is created out of thin air by commercial banks when they make loans.4 Bank money exists only inside the retail circuit.

d. Reserves: Reserves are electronic (or digital) money that is created out of thin air by the Federal Reserve when it makes loans or buys assets. Reserves exist only inside the wholesale circuit.

2. The two tiers or circuits in our monetary system

When we speak of a monetary circuit, we mean a circuit or network that includes one class of money issuers and a plurality of money users. To transact their business, ordinary people use money that is created in the retail circuit. So do all businesses that are not commercial banks. The reason commercial banks are excepted from using money in the retail circuit is that they actually create the electronic money used in that circuit, in the form of legal IOUs. Thus, commercial banks are not allowed to spend their own IOUs—a kingly privilege that is forbidden to them.

But if commercial banks cannot use retail money to transact their business, what form of money do they use? The answer is that commercial banks transact their own business in money created in the wholesale circuit. In the wholesale circuit, the money issuer is the Federal Reserve (actually the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks), which issues reserves. Reserves are thus used by commercial banks for transacting business. Reserves are also used by two other major classes of users: foreign central banks and the U.S. government, including, most importantly, the U.S. Treasury.

Why are there two different circuits of electronic money? The existence of two monetary circuits stems from the fact that in the U.S. and indeed throughout the world, money is created as debt. Legally, as noted above, the money used in the retail circuit is an IOU from commercial banks to users of such IOUs as money in the retail circuit.

If the debt-based monetary system were limited to a single circuit, it wouldn’t work, for at least two reasons.

First, if commercial banks were allowed to use their own IOUs as money with which to buy assets, the monetary system would explode instantaneously as commercial banks issued money ad infinitum.

Second, if commercial bank B were to accept an IOU of commercial bank A as “money,” taking bank A’s liability onto its balance sheet as if B had issued that IOU itself, there would need to be a way to balance out the transfer of liability from A to B with a corresponding asset.

The corresponding asset could be cash, of course, because cash is not a liability of any commercial bank; it is a liability of the Federal Reserve. But cash is physical, and what is needed to balance out the retail A-to-B bank transaction is an electronic asset equal in value to the IOU. That is where reserves come in.

The essential function of reserves is to “settle” transactions between banks so that bank B will honor bank A’s IOU as its own.5 Reserves are needed because commercial banks cannot simultaneously issue money and use that money without the system blowing up. A two-tiered monetary system makes it possible to handle the dual nature of commercial banks, that is, as issuers and users of money.

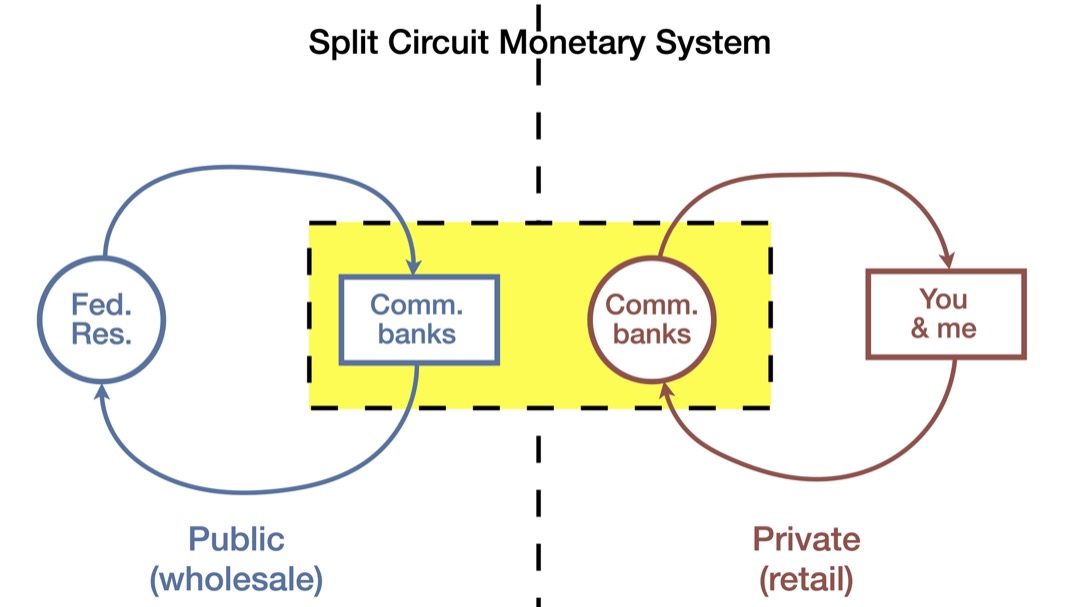

In one tier, the wholesale tier, the Fed issues reserves as money, which are used by commercial banks. And in the other tier, the retail tier, commercial banks issue money. A simplified diagram illustrating how commercial banks are the linchpin of the two-tiered or “split circuit” electronic monetary system6 is as follows:

Figure 1: Commercial banks are the linchpin of our split circuit monetary system, operating as money issuers in the retail circuit and as money users in the wholesale circuit.

The above diagram is highly simplified. Users of money in the retail circuit or tier (depicted as “You & me” above) include people, businesses, non-profits and foundations, and really any entity that is not a commercial bank that issues money. Thus, this also includes financial businesses, insurance companies, hedge funds, and even credit unions and savings and loans—none of which create money out of thin air as commercial banks do when they lend money. Money users in the retail circuit do indeed lend money, but when they lend, they are dispossessed of the money lent. This isn’t the case with commercial banks.

3. Special entities in our monetary system

There are a few special entities operating in the two-tier system that are worth mentioning briefly here.

a. U.S. Treasury

As noted above, the Treasury has an account at the Fed. It also has any number of accounts at commercial banks in the retail tier. The Treasury occupies a unique position within the two-tiered system. When the Treasury sells an asset to the Fed and has its deposit account at the Fed credited, the Treasury can then write checks on that account to pay people and businesses who bank in the retail tier. When this happens, the Treasury’s account at the Fed is debited in the amount of the check, and the Fed transfers reserves in the amount of the check to the payee’s commercial bank, which then credits the payee’s account at the bank with the amount of the check. In this way, it “looks” like reserves are jumping from the wholesale circuit into the retail circuit. They aren’t.

b. Savings and loans (S&Ls) and credit unions

These institutions use commercial bank money in the retail circuit just like the rest of us. Unlike commercial banks, however, these institutions do not create money out of thin air. Like the rest of us, they can only lend out previously accumulated or pre-existing money, and will be dispossessed of that money for the term of the loan. However, many (but not all) savings and loans and credit unions are unlike the rest of us in one important respect: they have accounts at the Federal Reserve. The purpose of these accounts is to settle transactions involving commercial bank money. Smaller savings and loans and credit unions that do not have accounts at the Fed (and thus no reserves with which to settle transactions) have a sponsoring bank, that is, a commercial bank that basically serves as the agent for these institutions in the Federal Reserve.

c. Cryptocurrencies and stablecoins

Cryptocurrencies are not money but rather are intangible non-monetary assets whose values fluctuate. Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies that are backed (supposedly) by another asset, often a fiat currency like the U.S. dollar, in an effort to reduce price fluctuations. One way for a stablecoin issuer to “back” their issuance is to simply hold a bank account with a quantity of dollars that matches the issuance of stablecoins.

d. Cash

Cash (Federal Reserve notes) occupies a special position in the monetary system in that it’s issued by the Federal Reserve and used in both the wholesale monetary circuit (for example, to settle bank money transactions between customers from two or more commercial banks) and the retail circuit. While people and businesses that transact their business in the retail circuit cannot spend or receive reserves (because they do not have accounts at the Federal Reserve), the same is not true for cash. Cash represents money to commercial banks and non-commercial-banks alike.

4. Large-scale payment processing and settlement

There are several transaction settlement and payment processing systems in place under the current monetary system. Some of the largest ones are described here.

a. Fedwire

Fedwire is a wholesale (commercial bank to commercial bank) settlement system that allows banks to settle retail transactions between one another in reserves. For a visual demonstration of why the settlement process is necessary, see “Wherefore Art Thou, Reserves?” starting at 16:30.7 Last year, Fedwire settled over 180 million transactions totaling $840 trillion.8

b. ACH system

The ACH (Automated Clearing House) system processes retail payments, including direct-deposit paychecks, recurring bill payments and deductions, and other large-scale systematic payments. Because these payments are akin to transfers between two bank customers of different banks (like a wire transfer), they involve both bank money at the retail level and reserves at the wholesale level for purposes of settlement. Not surprisingly, therefore, the ACH system is run by both The Clearing House (owned by 23 banks and operating as a non-profit) and the Federal Reserve. Because it serves retail instead of wholesale users, the ACH processes a much greater number of transactions (26 billion last year) than Fedwire.

c. CHIPS

Like Fedwire, CHIPS processes transactions for purposes of wholesale settlement. It differs from Fedwire in that it primarily processes cross-border payments and is run by The Clearing House. The name CHIPS in fact is an acronym for Clearing House Interbank Payment System. Last year, CHIPS processed 120 million transactions totaling $530 trillion.

d. Venmo and Zelle, etc.

Person-to-person digital retail transactions are an increasing presence in the retail monetary system. Last year, at 15 billion transactions processed, Venmo came closer than ever to processing as many transactions as the venerable ACH system, totaling $159 billion. Zelle was a distant second with 1.2 billion transactions, albeit at a remarkably higher dollar volume—$309 billion. Venmo is owned by PayPal, while Zelle is owned by Early Warning Services, a bank-owned utility along the lines of Clearing House.

5. What makes the Federal Reserve top dog in our monetary system

While both the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks and the 4,357 commercial banks9 in the U.S. monetary system issue money, the Fed is the legally superior institution despite the fact that there is far more retail money (about $17 trillion) than electronic wholesale money (about $6 trillion). This is so for two basic reasons.

First, the Federal Reserve is a principal regulator of the commercial banks. See generally Federal Reserve Act, 12 U.S.C. § 221 et seq. The Fed can revoke the charter of any member bank in violation of the Federal Reserve Act or regulations under the Act.

Second, commercial banks can be bankrupted (technically, put into resolution) despite their ability to create money. This is explained in a law review article by a team of international legal scholars as follows, using the astonishingly simple example of a single bank customer’s rights with respect to his deposit account at the bank:

If the customer demands settlement of the debt (payment of the deposit balance), the banker has a limited number of choices. The banker can settle its debt to the customer by transferring deposit balances held in its central bank reserve account to another bank that holds another account of this customer, or by delivering currency (bank notes) to the customer which the customer must accept pursuant to legal tender law. If reserves or bank notes cannot be obtained from the commercial bank’s own vault, the central bank or the private market, the customer can take steps to liquidate the bank.10

The same cannot be said of the Federal Reserve. The Fed cannot be bankrupted because its “liabilities” are not genuine liabilities in the legal sense. As we just saw, a commercial bank cannot freely issue IOUs (bank money) because the customers to whom those IOUs are issued can demand that the bank produce cash or transfer the IOUs to another bank (requiring the bank to produce and then transfer reserves). In either case, the bank must produce a form of money that it cannot conjure out of the thin air.

But the Fed is different—at least since August 15, 1971, when any gold-backing requirements were eliminated as a matter of law. Since then, the Fed can issue as many IOUs as it wants without fearing redemption demands for assets that it cannot freely manufacture itself. As the foregoing law review article put it:

As a matter of legal and institutional reality, central banks are in an entirely different position. The holder of CBM [central bank money, i.e., IOUs from a central bank] can never ask for repayment of that CBM in anything but CBM, making the ‘liability’ a self-referential loop with no terminus, and furthermore, central banks are (quantitatively) unlimited by law in the amount of reserves they can create. Together, this means that crediting a commercial bank’s reserve account or issuing a banknote does not create a ‘liability’ of the central bank in the way that a commercial bank deposit creates a liability for the bank.11

This legal distinction between the Fed on the one hand and commercial banks on the other hand is important in the discussion of CBDCs for two reasons. First, what the Fed is proposing to do by introducing CBDCs into the retail level is to compete with the banks it regulates. This is akin to changing the rules of Major League Baseball to allow the New York Yankees to umpire the games it plays against other teams. The outcome is quite predictable.

Second, by entering the retail monetary space directly, the Fed does so as the legally superior party offering a legally superior form of money—one that cannot be put at risk by insolvency. It is only a matter of time before retail users figure out as much, if they don’t intuit as much on their own, spelling the inevitable end of money issuance by commercial banks at some point in the future. At that point, there will no meaningful legal distinction between commercial banks and ordinary financial intermediaries, which can only lend money that is pre-existing rather than by creating the money lent.

C. The Current Monetary Problem

Central banks are pushing central bank digital currencies as a way to solve any number of “problems,” such as “financial inclusion,” the need for more efficient cross-border payments, the unfairness of a system that finds many people unable to participate (“the unbanked”), and so on. Every one of the “problems” that supposedly will be solved or ameliorated by CBDCs according to these central bank narratives, however, is a hobgoblin. Indeed one doesn’t need to venture beyond the ranks of central bankers themselves to find CBDC skeptics.12

This does not mean, though, that no monetary problems exist—they most certainly do. But the very real monetary problems that do exist are the handiwork of the central bankers themselves, who have invented a series of scapegoat problems, complete with the crocodile tears of central bankers sitting behind Bloomberg terminals in New York, that just so happen to draw one’s attention from the real problems, one surefire historical solution to which involves the elimination of central banking.

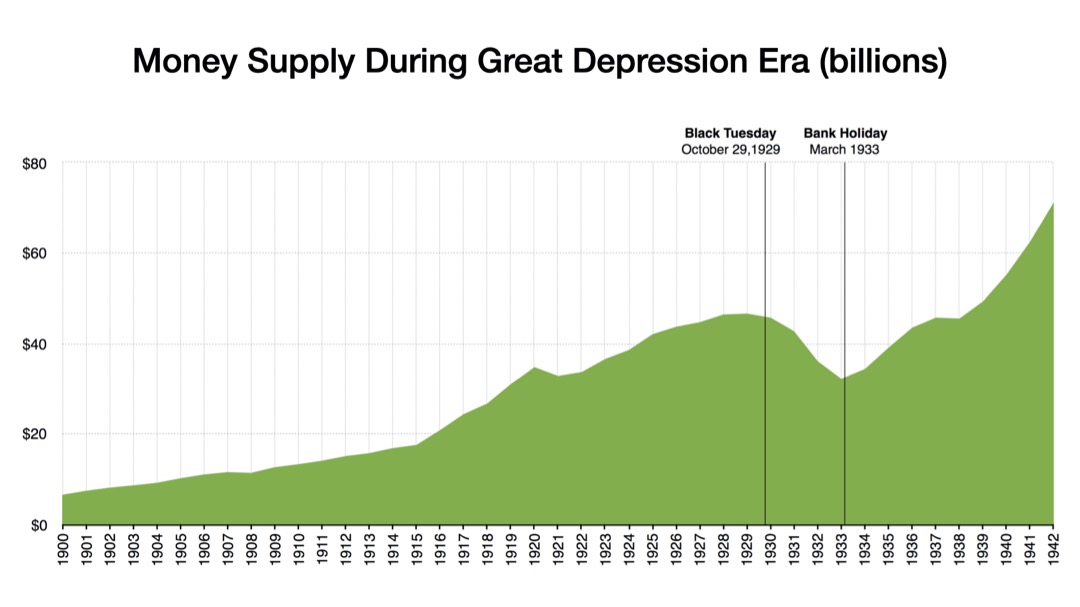

To fully understand the current and very real monetary problem that arises from a money supply that is debt-based, one must first appreciate the central role that the retail money supply plays in economic downturns. In short, economic downturns are characterized by the disappearance of money: “no one has any money” is the catchphrase of lean times. The depth of the Great Depression was characterized by a collapse in the retail money supply of over 30%:

Figure 2: A declining money supply is what depressions are made of.

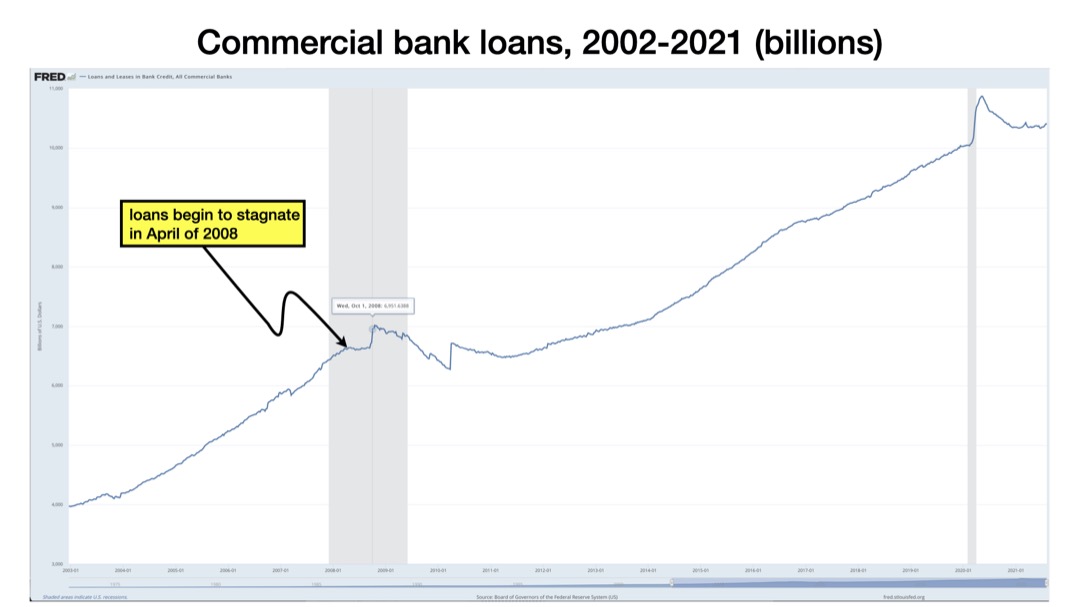

In the graph above, note that the retail money supply had first stagnated and then begun its decline just before the stock market crash on Black Tuesday. In our debt-based monetary system, new money is created when banks lend, and it is destroyed when loans are (1) paid back, (2) defaulted on, or (3) cancelled. Thus, unless banks continue issuing new loans at a faster rate than loans are paid back, the money supply is going to stagnate, which is going to show up in the economy first as a recession and, if left unchecked, then result in a depression. Stagnant lending activity by commercial banks is a serious warning sign. This is exactly what happened during the run-up to the global financial crisis of 2008:

Figure 3: Commercial bank lending was the canary in the coal mine before the 2008 crisis hit.

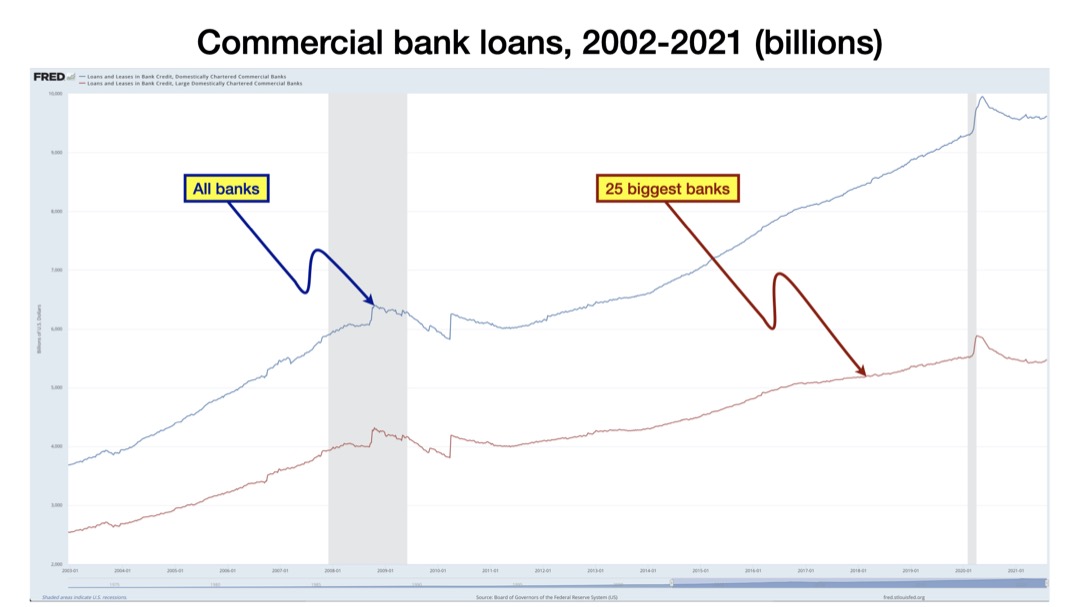

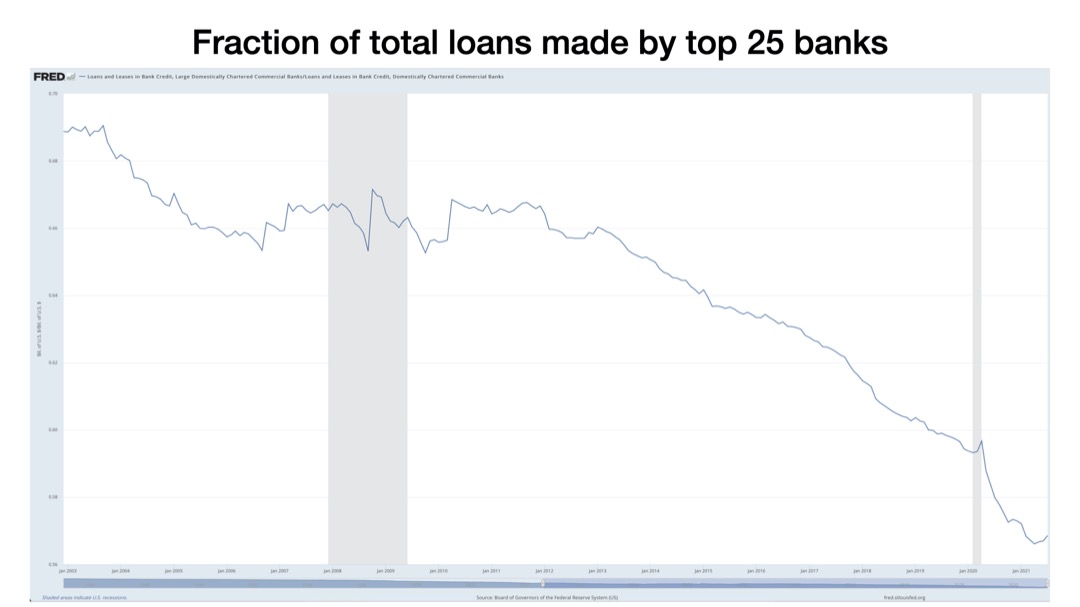

As important as commercial bank lending is to the economy, there is a long-term trend in the U.S.—a policy trend—that has the very strong tendency to reduce lending. That trend is the consolidation of smaller banks into larger banks by merger, and it’s a trend that is actively promoted by the Federal Reserve. Thus we begin to see here the first contours of the dynamic at work with CBDCs: the Federal Reserve creates a problem and then proposes a “solution”—perhaps acknowledging the problem, perhaps identifying some other alleged problem—that exacerbates the problem and that increases the Fed’s power and control.

Along these lines, one major force behind stagnant bank lending is the consolidation of banks into mega-banks. The Fed is a big proponent of making banks bigger in the name of “efficiency.” In fact what the Fed is encouraging with its pro-mega-bank mania is sharply less lending, which is apparent from the following chart comparing commercial bank lending for the 25 largest banks (red line) with the commercial banking sector as a whole (blue line). Notice how much flatter the trend line is for larger banks (red):

Figure 4: Large commercial banks engage in less lending than their smaller counterparts.

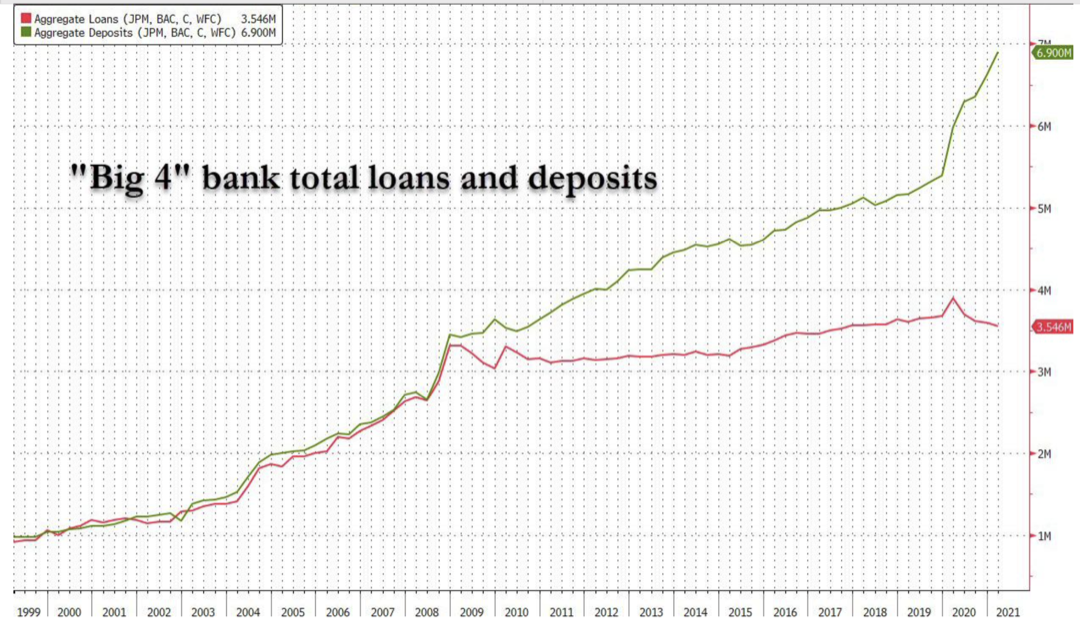

The problem is even worse when one considers the top four banks as opposed to the top 25 banks.13 Zerohedge.com ran an article in April 2021 pondering the mystery of how deposits at the top four banks could be rising in the absence of bank lending.14 Despite the article’s complete failure to identify the actual agent for increasing deposits in the absence of lending (i.e., quantitative easing as the Federal Reserve has practiced QE since the onset of the pandemic),15 the graph of deposits and lending at the four biggest banks in that article reveals that lending by the top four banks has not increased at all since the global financial crisis:

Figure 5: Lending (red line) by the top four U.S. banks reveals what a drag on the economy they are.

This brings up another Federal Reserve policy that independently and vastly augments bank size so as to exacerbate the chokehold on lending to the detriment of the real economy—bailouts.

In 2008, while attention in the financial world was fixated on the $700 billion bailout of the mega-banks by the U.S. Treasury via the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), the Fed was secretly engaged in a multi-trillion dollar bailout of those same mega-banks itself.

Whereas the top four banks received $140 billion in TARP funding,16 they received over $6 trillion in zero-interest loans from the Federal Reserve.17 The officially stated reason for bailing these banks out was that they were needed to support lending to Main Street. In view of the failure of these institutions to increase lending at all in the dozen-plus years since the global financial crisis, the Fed’s pro-bailout policy can fairly be described as a disaster—at least if the Fed’s reason for bailing out these banks can be credited.

One must wonder about the latter in view of the Federal Reserve’s active encouragement of bank mergers, a policy that undeniably suppresses lending activity. This policy has drastically reduced the ranks of the very banks most likely to engage in lending to Main Street (where most new jobs are created), namely, smaller banks. In December 2002,18 there were 7,887 commercial banks in the U.S. When the global financial crisis hit in September 2008, that number was down to 7,146, and today it stands at 4,357.19

Figure 6: Despite massive bailouts and growth via mergers, mega-banks are poor lenders.

By adopting policies that prop up failed mega-banks, the Fed has created a climate where the weakest banks (i.e., the biggest ones) continue growing through mergers and bailouts despite—or perhaps due to—the fact that they make the worst lenders. The 20-year chart of the percentage of all loans coming from big banks is astonishing, as Figure 6 makes clear.

The correlation at work here is clear: the largest banks are more reluctant to make loans, which in our presently configured monetary system has the effect of suppressing loans. As noted above, this tendency toward less lending becomes even stronger when the “largest” banks under consideration are reduced from the top 25 to the top four.20

And yet despite the tendency of larger banks to ignore their remits by seriously reducing their lending activities, the Federal Reserve is zealous in its promotion of bank consolidation: in the last 15 years, the Fed approved 3,576 bank mergers without denying a single one.21

Thus the Fed’s big bank bias and the merger mania it has birthed have given rise to a stagnating economy where big banks don’t make loans (out of fear or otherwise), and new businesses are discouraged as huge banks are kept alive with a morphine drip of assistance from the Federal Reserve.

As shown in The Going Direct Reset, the Federal Reserve has intervened directly into the retail monetary space through structured quantitative easing maneuvers that use the capacity of commercial banks to create retail dollars so as to match, dollar for dollar, every dollar that the Fed creates in reserves. Those new retail dollars are then used to buy assets like Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, whose sellers then deploy that retail money in search of higher-yielding assets.

While this has “helped” to inflate the retail money supply to the tune of $3.5 to $4 trillion, that new money has simply handed cash to billionaires in exchange for low-yielding assets, which money is then promptly put into riskier assets like the stock market. This does next to nothing for Main Street but contributes massively to the wealth gap.

Having thus created every one of the foregoing problems itself—each time in the name of helping the broader economy—now comes the Federal Reserve again with promises of help. Starting at the lower rungs of the broader economy with “the unbanked,” this time the Fed’s most radical measure yet is to “help” everyone, namely, with a central bank digital currency.

In short, the system isn’t working (at least for its stated purpose), and the Fed is now taking matters into its own hands with CBDC.

D. The CBDC Solution

As we saw above, the progressive concentration of commercial banks into a few mega-banks supplying a significant fraction of the money supply has painted the retail monetary system into a box: simply put, those banks are now too large and are not making new loans at a rate sufficient to satisfy demands for money, which has left the monetary landscape tending toward depression.

One does not have to look any further than the pandemic to see the concerted push to harm Main Street and help the Fed’s Wall Street allies. While Main Street businesses (but never big-box retailers) are forced to shutter their doors in the name of “flattening the curve” or whatever other bromide the Fed chooses to hide behind, the Fed in response launched a $3.5 trillion quantitative easing program in 2020 in which that sum of money was used to gin up demand for assets like Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. Thus Main Street is harmed from two different directions—first from business closures and second with much higher deficits and debts, which are invariably used to justify further austerity measures like higher taxes and less spending.

In keeping with historical patterns, central bankers are loathe to admit the real problem—which they play the leading role in creating—and now purport to come to the rescue with a solution that will vastly increase their power. As usual, however, the central bankers must also pitch a series of “problems,” none of which do they genuinely care about, and indeed they are doing so now with speeches and papers, for example, about “the unbanked” and the need for efficient cross-border payment systems, to which of course CBDCs are now promoted as the solution.

The Fed cannot just switch over to a new retail monetary system all at once; the task is so colossal as to make the Fed in all its hubris blanch. Thus the switch to CBDC will have to be done incrementally, in stages.

Indeed, while the commercial banking system appears unable to sustain the monetary framework necessary to support the economy any longer, even central bankers are careful to point out that the commercial banking system will not be scrapped all at once. For one thing, that system and its massive infrastructure has a very long history of supporting hundreds of millions of ordinary people and businesses.

Still, any shift to CBDC is a watershed event. By creating retail digital money in the form of CBDCs, central banks are directly encroaching on what was formerly the exclusive territory of commercial banks. Thus there are big questions about what role(s) commercial banks will play once central banks begin issuing CBDCs.

These and other issues are now considered in turn.

1. The cash bogeyman

In one narrative advanced by central banks in attempting to explain why CBDCs are necessary, central banks argue that the use of cash has been diminishing materially. As one recent research paper from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) framed the issue: “cash is being used less and less as a means of payment, and the surge of online commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated this development. Should this trend prevail and cash no longer be generally accepted, central banks would have to develop a digital complement, an accessible and resilient means of payment for the digital era.”22

That “reasoning” by the BIS makes little sense: if cash loses widespread acceptability, why do central banks have to step in at all when other means of electronic payment—via commercial banks—already exist and have a long track record? The conclusion of the BIS that CBDC is necessary simply doesn’t follow from its own premise.

The BIS gets closer to the truth in the next example given in the same research paper, but it begins with the same cash feint:

[A] concern is that if the use of cash decreases further, to the point where it loses its universal acceptability, a financial crisis could create havoc by leading to situations in which some financial institutions have to freeze their clients’ deposits, thus preventing their clients from paying their bills.23

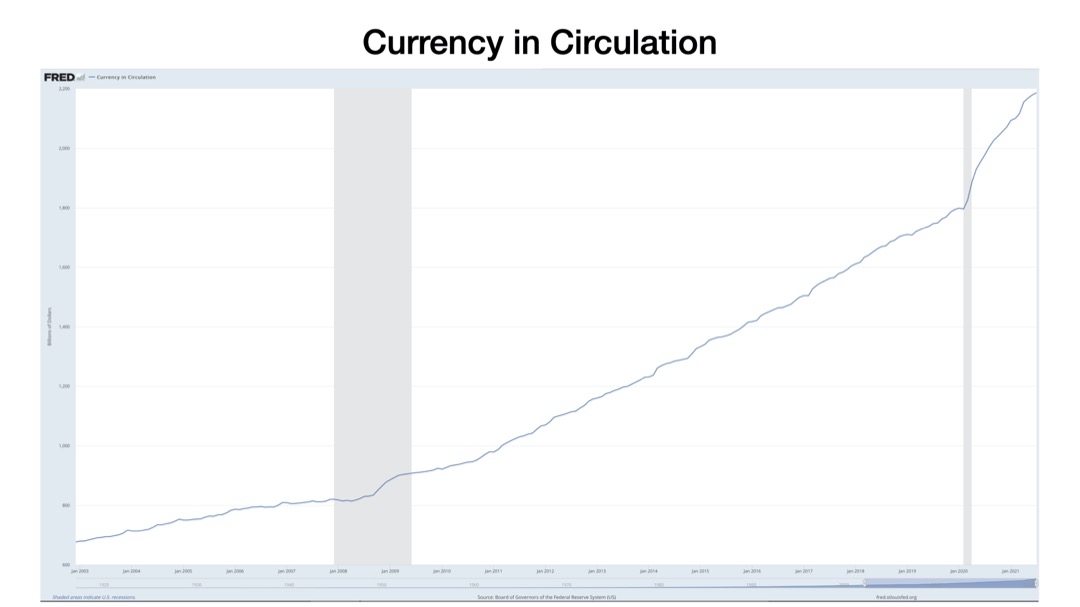

As a threshold matter, the premise of that “concern”—that the use of cash is decreasing in the first place—is patently false:

Figure 7: Cash is more popular now than ever.

The “disappearing cash” bogeyman in this latter BIS narrative appears intended to take attention away from the real source of the problem in that very same narrative: financial institutions needing to freeze their clients’ deposits (whether or not spurred by a financial crisis).24 But the BIS won’t own up to what exactly necessitates a deposit freeze, aside from vaguely positing the onset of some unspecified “crisis.”

The real reason that a bank would need to freeze customer deposits is that those deposits represent liabilities on the balance sheet, liabilities that the bank would be all too happy to see transferred to other institutions. However, liabilities don’t get transferred away when a customer moves his money to another institution. Instead, those liabilities get deleted and, more importantly, a corresponding amount of reserves—balance sheet assets—get transferred to the recipient bank, which must then create a new deposit account (a liability) in the amount of the transferred reserves.

Thus, by “freezing” deposits, what a financially insecure bank is really doing is stanching the outflow of reserves and thus preventing a bank run. Doing this allows a struggling bank—should other asset valuations decline enough to wipe out the bank’s equity altogether and threaten bankruptcy—to make preparations to “bail in” deposit accounts by reducing their size by some uniform amount to save the bank.

Put bluntly, the real concern of the paper’s authors appears to be that there are commercial banks, very likely including one or more mega-banks, that are at risk of failing, in which case those mega-banks would not be undertaking any significant lending activity for fear of adding exposure and risk—exactly as we saw in the previous section. On this score, the BIS advances the risks that “the intermediary [commercial banks] might run into insolvency, be fraudulent, or suffer technical outages” as good reasons for adopting CBDCs.25

Whatever is motivating central bankers to adopt central bank digital currencies, it has little to do with cash. After all, it is the central banks that issue cash, and thus it is they themselves who directly control how much cash is in circulation. A credible motivation for central bankers to move to CBDCs is something over which they lack control, such as the solvency of commercial banks and the amount of retail bank money in the system.

CBDC represents a way for central banks to shore up these deficiencies—regardless of how they choose to cast the narrative.

2. Exactly what collateral will back CBDCs?

At an October 2020 symposium sponsored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), both Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens were quick to acknowledge that CBDCs would represent the third liability on central bank balance sheets.

The first liability is cash, and the second is reserves, as we saw above. While the Fed (and all central banks) create these liabilities (IOUs) out of thin air, it doesn’t give them away for free. Instead, the Fed sells both of them in exchange for some asset, at which point both the IOU and the corresponding asset get logged on the Fed’s balance sheet, which gets updated weekly.26

The classic asset in these transactions is a U.S. bond, say, a 10-year Treasury note or a 30-year Treasury bond. These financial instruments are IOUs themselves, but bear a higher interest rate than the corresponding IOUs from the Fed.27 The “collateral” backing the governmental IOUs isn’t any physical or financial assets but rather is said to be the full faith and credit of the U.S., including its power to collect taxes.

The point here is that the asset backing “our” money (whether cash or reserves) is the IOU of the whole nation, just as the whole nation benefits from circulating money.

But what exactly will constitute the asset backing CBDCs?

On the one hand, it is possible that the asset that backs CBDCs will look exactly like the assets backing reserves and cash: it will be a U.S. bond, that is, an IOU from the whole nation.

On the other hand, the Fed started relaxing its rules on what kinds of assets satisfied the backing requirements when the global financial crisis hit and the Fed began accepting other types of assets, like mortgage-backed securities (MBS). As of August 12, 2021, fully 28.9% of the $8.3 trillion in total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet were MBS.28

To get around the full faith and credit requirement, the Fed notes that the MBS on its balance sheet are “[g]uaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae,”29 which are government-sponsored mortgage companies, which is at least one step removed from direct backing by the United States Government.

Since the guarantees of U.S. corporations can meet the backing requirement for assets on the Fed’s balance sheet, one must wonder whether the guarantees of individual U.S. citizens would work as well. Could people themselves, in other words, serve as the collateral for CBDCs issued to them by the Fed?

The available literature on CBDCs coming from the central banks never seems to address this question. The issues that central banks do choose to address when discussing CBDCs, though, put the issue just beneath the surface.

At an October 2020 IMF Symposium, BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens explained why central banks consider CBDCs a superior substitute for cash:

In our analyses of CBDC, in particular for the use in general… of general use, we tend to establish the equivalence with cash. And there is a huge difference there. For example, in cash, we don’t know, for example, who is using a $100 bill today, we don’t know who is using a 1000-peso bill today. A key difference with the CBDC is that central banks will have absolute control on the rules and regulations that will determine the use of that expression of central bank liability [i.e., use of CBDC], and also we will have the technology to enforce that.30

Later in that same symposium, Carstens made it clear—and was quite enthusiastic about the fact—that with CBDCs central banks will have the power to decline individual transactions.31

Indeed, much of the discussion by central bankers of how best to implement CBDCs arises from the fact that granular control and accounting is not only possible but seemingly inevitable, as we’ll see below.

For now, the point is that the mass collateralization of CBDCs, as by Treasury bonds, is by no means inevitable or to be assumed. We should, therefore, be aware of the fact that individual collateralization is possible, has not been taken off the table by central banks, and may be in the cards. This possibility is especially worthy of one’s consideration in view of the Pandora’s box of secondary financial products (like credit default swaps and other forms of Wall Street gambling) that might arise if CBDCs are collateralized in the same way as, say, mortgages—individually.

3. The role of commercial banks in a CBDC system

As shown above, commercial banks have become unable to support the money issuance needed to uphold the retail monetary system. With CBDCs, central banks are proposing to make up the monetary deficit left by the increasingly concentrated commercial banking system.

a. The Federal Reserve has already entered the retail money creation space

That process has actually begun already. As we saw in The Going Direct Reset, central banks began intervening in the retail money supply at the start of the pandemic, when the Fed dramatically increased its balance sheet by some $3.5 trillion—a process that forced the mirror-image creation of $3.5 trillion in the retail monetary system at the same time. The simultaneous and parallel creation of retail money at the initiation of the Federal Reserve had never occurred before and was the keystone of BlackRock’s “Going Direct” policy plan presented to the Fed and other major central banks on August 22, 2019.

A recent video by the author32 shows that the Going Direct plan was more likely to have gone into effect during the week of September 17, 2019—just three weeks after BlackRock published its plan—when a crisis in short-term lending markets forced the New York Federal Reserve to enter the overnight repo market.

In either case, even a casual comparison of money on deposit at the Federal Reserve (i.e., wholesale money, or reserves) with money on deposit with commercial banks (i.e., retail money, or bank money) reveals that the Federal Reserve has already invaded the retail money-creation space in a big way.

![]()

Figure 8: At some point (take your pick), retail bank deposits on account at commercial banks (red) began tracking wholesale deposits on account at the Federal Reserve (blue).

b. Without CBDC, the Federal Reserve’s ability to prop up the retail money supply is very limited

Though the Fed’s planned entry into the retail monetary space is evident from publicly available monetary data, the Fed’s ability to effect the creation of new money in the retail space faces a number of serious constraints that rule this route out as a viable workaround for the failure of commercial banks to meet the monetary demands of the retail space.

First, the new retail money created via the Going Direct method goes into the hands of huge asset holders, that is, billionaires and major financial institutions, who are selling their low-yielding assets (like Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities), getting new retail (bank money) in return, and investing that new money into higher-yielding assets like equities and special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). Indeed, BlackRock’s Going Direct plan expressly calls for “credit easing by way of buying equities.”33

Even if successful, asset swaps like the ones proposed by BlackRock’s Going Direct plan, of course, do not contribute to GDP. They do serve, however, to severely exacerbate inequality. This was evident throughout the pandemic as billionaires doubled and tripled their wealth as the result of the Fed’s adoption of BlackRock’s plan. For this reason alone, BlackRock’s Going Direct plan has no long-term viability—at least without risking open revolt.

Second, the linchpin of the Going Direct plan is the ability of commercial banks to “clone” the Fed’s issuance of new reserves by creating a twin issuance of new bank money. This process is explained in The Going Direct Reset.34 Without the commercial banks as intermediaries between the Fed and the retail money supply, the Going Direct plan will not work. Moreover, the Going Direct method inherently means that commercial banks expand the liability side (retail bank money) and the asset side (wholesale reserves) in lockstep with the Fed’s creation of new reserves. Unlike the Fed’s ability to expand reserves indefinitely, however, the balance sheets of commercial banks cannot be expanded without taking on more risk and/or running afoul of regulatory limits like those in Basel III.

Third, the ability of the Fed to lower interest rates and thereby induce more lending by commercial banks in the retail sector is, if not tapped out, approaching that point rapidly. Interest rates were near-zero for the decade-long run-up to September 2019, which is indeed when the Fed was forced to adopt BlackRock’s Going Direct plan to expand the retail money supply in a way that BlackRock itself described as “unprecedented.”

Moreover, it is important to realize that it’s the Fed’s policies themselves—as opposed to market forces—that are responsible for many woes in the retail monetary space. For one thing, the Fed is almost rabidly in favor of bank consolidation. For another, as bank mergers result in gargantuan mega-banks, those banks are then bailed out and provided with the steady drip of Fed money via quantitative easing. For yet another, the Fed turns a blind eye to crime and fraud perpetrated by the mega-banks, which by definition (since a crime harms the public, prosecution is a matter for the state) acts to the detriment of everyone else. In short, the Fed has gone out of its way to ensure that counterproductive policies are both implemented and entrenched.

By way of that background, BlackRock’s Going Direct plan is part and parcel of greater Fed malfeasance: it always was just a temporary workaround for the Fed to effect the addition of money to the retail money supply as the Fed takes greater control over the economy. Eventually, the Fed was going to have to take matters into its own hands by adding new retail money itself. That is the essence of CBDCs.

c. Where do banks fit in the central bankers’ plans for CBDC?

At first blush, it might seem that because the Fed intends to directly issue retail money, and thereby begin to compete with commercial banks, the Fed might be planning to eliminate commercial banks. That does not appear to be the case, however, not only for the reason cited above (the Fed wants to add money to the retail monetary tier, not dismantle and rebuild that tier), but based on statements from the central bankers themselves.

Central bankers recognize that the long-standing experience of commercial banks with countless locations where people reside gives the banks major comparative advantages over the Fed when it comes to day-to-day issues regarding money. For this reason central bankers very much want commercial banks (i.e., the private sector) to be involved with the CBDC ecosystem:

The rationale for the private sector’s involvement is the commitment to market-based solutions: good investment decisions often require specific local knowledge, while efficient provision of services requires open and competitive markets. One aspect is that a bank that invests by making loans must know or be able to estimate creditors’ solvency to price the associated risk. Public sector institutions might not have this knowledge to the degree that local and specialized private investors do…. Another aspect is that competitive markets are also contestable, and allow many firms to compete, improving economic efficiency. A corollary of the free market idea is that the customer-facing side of money and finance, as well as continued innovation in this field, is best left to the private sector.35

Moreover, and consistent with the notion that central banks want to expand rather than supplant the existing capacity for retail money issuance, central bankers have advised that “the economic design of a CBDC should hence allow commercial banks to keep their intermediation role between savers and investors.”36

On the other hand, some Fed policies seem calculated to nudge out Main Street financial institutions in the name of advancing central bank digital currencies—a process that may indeed be part of the Fed’s true agenda as it pushes toward CBDC. In this regard, some CBDC proposals from the Fed do seem like wolves in sheep’s clothing. Whereas people in a position to know how CBDCs will affect community banks generally disfavor CBDCs inasmuch as “a digital dollar could fundamentally disrupt the banking sector’s business model because community banks might not be able to use CBDCs stored in electronic wallets,”37 the Fed seems intent on advancing community banks as part of the CBDC ecosystem—at least in terms of harvesting intel: “Engaging broadly with financial institutions of many types, from global systemically important banks to local community banks to internet-only banks, would inform policymakers on potential impacts, benefits, design considerations, and policy requirements.”38 Critical thinking is the most prudent course here as with any bold new proposals coming from the Federal Reserve.

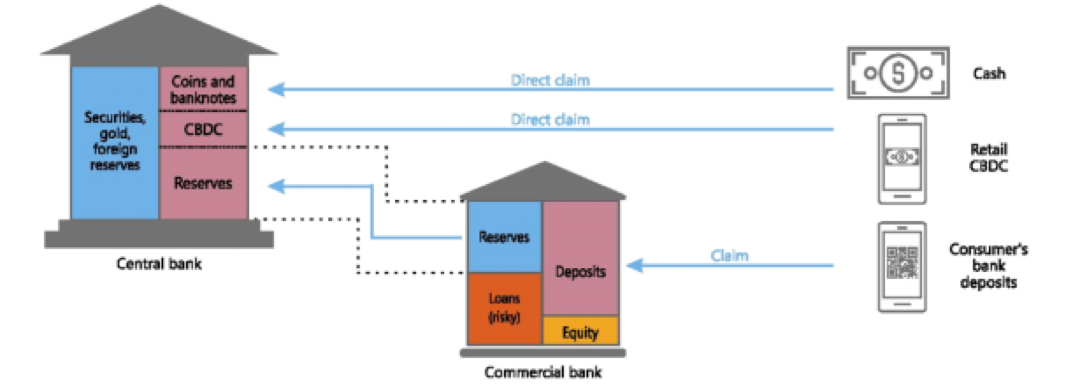

In any case, as presently envisioned by central bankers, the CBDC ecosystem will be grafted on as a middle layer within the current two-tier monetary architecture, as this diagram from a recent BIS paper illustrates:39

Figure 9: In the CBDC system as contemplated by central bankers, retail CBDC will exist alongside both cash and electronic bank accounts (right side), representing no more than one change to the existing two-tier money issuance system, namely, as the third liability on central banks’ balance sheets (the first two being cash and reserves).

Thus, the real question isn’t whether commercial banks will remain viable in the contemplated CBDC system (they will), it’s what role private banks will play in that system. We address that issue in the next section.

E. Implementing CBDC

It should be noted at the outset that any discussion of how CBDC will be implemented is inherently speculative to a significant extent simply because the Federal Reserve has not yet issued a CBDC and is unlikely to do so for several years.40 Nevertheless, we can do a fair job of describing what a CBDC system is likely to look like based on public statements about such a system by central bank officials. We consider these in turn after first touching on one legal hurdle the Fed faces before it can issue so much as the first U.S. dollar in CBDC.

1. The Federal Reserve will not attempt to implement a CBDC without

congressional approval

Under the current Federal Reserve Act, the Fed may issue both physical Federal Reserve notes (to commercial banks for use by their retail customers) and digital reserves to account holders at the Fed, including commercial banks (to settle retail interbank transfers). Because the Fed lacks any express statutory authority for issuing an electronic liability to retail users, it is next to certain that the Fed will seek congressional amendments to the Federal Reserve Act before proceeding to issue a CBDC. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has unequivocally stated as much on several occasions, for example:

[W]e would need buy-in from Congress, from the Administration, from broad elements of the public…we would not proceed with this without support from Congress, and I think that would ideally come in the form of an authorizing law, rather than us trying to interpret our law to enable this.41

Assuming that congressional approval will be forthcoming when the time arrives, we now consider what a practical implementation of CBDC in the U.S. might look like, taking into consideration various public statements by central bank officials.

Generally speaking, these statements fall into one of two categories. First are those official pronouncements that can probably be taken at face value because they are technical or operational in nature and thus are not controversial. A second category of official statements, though, should be regarded with great skepticism because they do not comport with what is generally known about central bank policies. This second category of pronouncements is nevertheless valuable because such statements are likely indicators of the direction in which the Fed is leaning on certain issues.

2. Credible official statements as to operational details of CBDC

Several straightforward matters concerning the operational details of a CBDC system can be gleaned from statements made by central bankers.

a. CBDC will be the third liability and second digital liability on central bank balance sheets

Central bankers are in widespread if not consensus agreement that CBDCs will represent the third liability on central bank balance sheets. Both Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens were quick to make this point at an IMF-sponsored symposium in October 2020.42 Likewise there is no dispute either that (1) CBDC will be digital (as its name implies) or (2) CBDC will circulate in the retail circuit of the two-tier monetary system that is prevalent worldwide.

b. Central banks are highly unlikely to interact directly with retail CBDC users

There is widespread agreement among central bankers that central banks should avoid taking on huge complexities that can be handled by existing systems. Along these lines, because CBDCs will function as digital money in the retail circuit, which in the U.S. comprises tens of millions of businesses and hundreds of millions of people, there is general agreement as to the fact that the infrastructure necessary to support CBDC as a viable monetary option will be inordinately complex. This is consistent with the view of central bankers who recognize that the existing retail monetary structure wields a major advantage over central banks in terms of local knowledge.

For this latter reason, it is almost certain that the Fed will forego attempting to implement what is known as a “Direct CBDC” system, meaning one in which CBDC users maintain accounts directly with the Federal Reserve, which in turn manages the CBDC payment system by itself with no intermediary service providers or banks.43

As a practical matter, this means that retail money users would be interacting with a financial intermediary (such as a bank or fintech company) rather than the Fed itself in a CBDC system.44 In such a system, the retail user would keep his CBDC on account at the intermediary, which in turn would be required to keep a matching amount of CBDC on account at the Fed. The purpose of this arrangement is two-fold. First, the Fed would not be burdened with the inordinate task of handling retail commercial transactions but would keep tabs on the system at the wholesale level by interacting with the intermediary CBDC institutions.

The key difference between CBDC intermediaries and commercial banks in today’s monetary system is that the former would function as true intermediaries—not as money issuers like commercial banks—and would not book CBDC transactions on their balance sheets. As BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens puts it:

Users could pay with a CBDC just as today, with a debit card, online banking tool or smartphone-based app, all operated by a bank or other private sector payment provider. However, instead of these intermediaries booking transactions on their own balance sheets as is the case today, they would simply update the record of who owns which CBDC balance…. In this way, the central bank avoids the operational tasks of opening accounts and administering payments for users, as private sector intermediaries would continue to perform retail payment services.45

Second, the requirement of having the intermediary keep matching amounts of CBDC on account at the Fed would protect retail users in the event of intermediary insolvency or default by ensuring that the customer’s CBDC would be honored.

The importance of the fact that CBDC intermediaries are very unlikely to be limited to commercial banks cannot be overstated. Commercial banks are the only institutions in the retail space that can issue money; this is their defining feature. By deciding to allow non-commercial-banks to act as intermediaries, the Fed will be opening the sluice gates to competition between a rash of players that are replete with unsavory actors, including fintech, hedge funds, insurance companies, shadow banks, and the like. The internecine warfare likely to be set off in the ensuing race to the bottom may in a strange and assuredly unintended way work to humanity’s advantage in the same way as a gunfight among criminal gangs.

In any case, there are very important policy decisions to be made about what powers the Fed is likely to delegate to any such intermediaries, and in our view the likely outcome of some of these decisions and details can be gleaned from the second class of official statements.

3. Official CBDC statements about policies that strain credulity can nevertheless indicate which way central bankers are leaning on certain issues

In the discussions of CBDC, members of the Fed and other central banks are prone to offer policy directives that on the one hand suffer from a basic lack of credibility but that on the other hand may indicate the direction in which central banks may be leaning or which of a few possible outcomes they might be inclined to choose. Four examples are of importance here.

a. Financial inclusion

First, “financial inclusion” is a catchphrase that almost invariably comes up in official discussions of CBDC. Financial inclusion is most often advanced as a reason for adopting CBDCs.46 In this connection, one will almost inevitably hear the term “unbanked” bandied about—as in CBDCs represent a “solution” to the “problem” of people whose credit is so poor that they cannot get bank accounts—creating the “need” for central banks now primed to step in with assistance in the form of CBDCs.

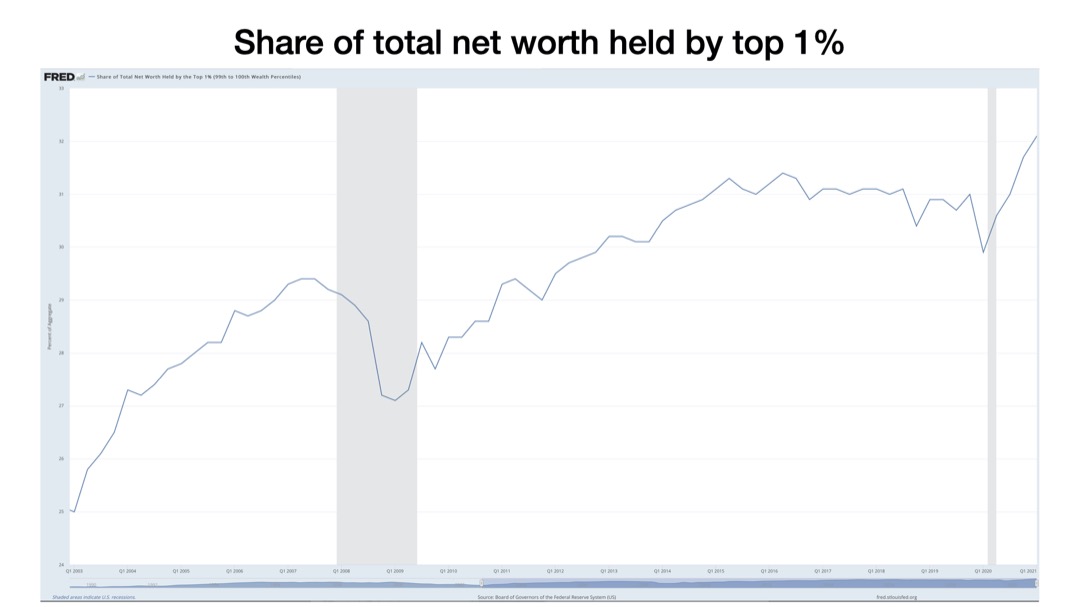

But the notion that central bankers are concerned with the poverty of the masses (or the masses’ ability to engage in retail electronic commerce) is completely risible, of course. Even a glance at the long-term trend in wealth skew is enough to make one wonder if the whole purpose of central banking weren’t just the opposite motivation as the one now put forward by central bankers, namely, to enrich the top 1% to the detriment of everyone else:

Figure 10: Federal Reserve policies seem designed to assist parties other than the poor.

Nevertheless, the insistent drumbeat of “inclusion” as a goal of CBDC to advance the interest of the unbanked can be fairly regarded as where the Fed’s efforts will be focused, at least initially, in implementing CBDC. Agustin Carstens himself has written that central banks intend to start small with CBDCs and to grow them as time goes on.47 Using the poor for a beta rollout before moving on to bigger game seems far more consistent with central bank policies than does anything motivated out of genuine concern by central bankers for the welfare of the downtrodden.

b. Universal Basic Income and “the unbanked”

Second, and relatedly, the focus on “the unbanked” is also consistent with increasing public discussions of universal basic income (UBI). Moreover, it fits in perfectly with the endless schemes, described by commentators like Alison McDowell, of major financial corporations to commodify and profit from programs centered on treating the poorest members of society as financial products to be wagered on.48 Every one of these schemes relies on data harvested from retail users, a factor discussed in greater detail below.

To be sure, the focus by central bankers on “the unbanked” should be regarded with total skepticism, given what “the unbanked” themselves have to say about it: while it is true that 5.4% of U.S. households are unbanked, fully three-quarters of those households reported that they “were not at all interested” or “not very interested” in having a bank account, according to a 2019 FDIC survey.49

The fact that central bankers are repeatedly invoking a policy that is completely pretextual, however, is a very useful tell as to where those central bankers are headed with CBDC in the near future, namely, toward data-harvesting from retail users, starting with the poorest members of society.

c. Privacy

A third pretext one continually hears invoked by central bankers—at least by Federal Reserve officials, anyway—is a concern over privacy, meaning (putatively) that the Fed is concerned with the legalities of prying too far into the private affairs of retail CBDC users. Jerome Powell voiced this concern at the October 2020 IMF symposium on CBDCs, reiterating the essential point he’d made in a letter to a congressional representative a year earlier.50

But again, the “concern” over the rights of ordinary people expressed by the Fed rings hollow in light of recent experience. For example, the Fed is the regulator of Wells Fargo, which in 2016 was caught creating “more than two million deposit and credit card accounts” in the names of its customers, who had no idea what Wells was doing behind their backs.51

If the Fed were really concerned about privacy, it might have filed at least one criminal referral for the two million separate criminal cases of identity theft perpetrated by Wells Fargo. The Fed filed none. In lieu of immediately seeking prison sentences, then-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen eventually got around to giving the bank a stern dressing down some two years after the bank got caught: “We cannot tolerate pervasive and persistent misconduct at any bank and the consumers harmed by Wells Fargo expect that robust and comprehensive reforms will be put in place to make certain that the abuses do not occur again,” she said.52 In addition, the Fed required the bank to replace three of its 16 board members.

Thus, the Fed’s invocation of concerns over privacy look much less like any genuine expression of concern for people’s rights and more like a weather vane indicating which direction the Fed is likely to turn with respect to later-arising issues. We will revisit the privacy issue below.

Along these lines, it is worth noting that the entire fintech industry hinges on the efficient harvesting of personal data. It is literally worth trillions of dollars. Indeed, it is difficult to find anyone who hasn’t repeatedly been confronted with pop-up ads on their computer directly stemming from activity that occurs away from the computer, for example, by talking on their mobile phone or just walking around and pausing to look at a store window. The collective message is clear: not only are you being watched but your data are being sold (since whoever is causing your situation-driven pop-ups to appear on your computer is doing so free of charge). CBDC will take the fintech data-harvesting game to a new and likely very dark dimension.

Moreover, as explained below, if privacy were truly a concern of the Federal Reserve, the Fed would push for a token-based CBDC system rather than one that is account-based. Instead, it is the other way around, as shown below. The issue of privacy could be used by the Fed, however, to justify the outsourcing of data-harvesting from personal accounts, necessary in the first instance in the name of fighting money-laundering and terrorism, to private intermediaries such as Amazon and BlackRock.

d. Cross-border payments

Yet another dubious justification frequently offered by central bankers in support of an alleged need for CBDCs is the necessity of effecting payments that cut across national boundaries. Indeed, the IMF hosted an entire symposium on CBDCs that lent this notion to the very name of that event—”Cross-Border Payments—A New Beginning.”53

The necessity or even usefulness of CBDCs to effecting cross-border payments, however, is regarded with a great degree of skepticism by some monetary professionals, to be sure:

It is very difficult to understand how adoption of cross-border CBDCs would solve or simplify current problems with cross-border payments. A token-based access system would seem to make matters even worse. Central banks could agree to exempt transfers of CBDC from all the regulatory and compliance requirements that currently complicate them, but they could take the same action under the current payments regime – and understandably have decided not to do so.54

Once again, the reason cited by central bankers seems to be at odds with their stated objectives. In the case of cross-border payments, there is another major and unspoken motivation for exaggerating the importance of this consideration, which is the removal of end users from the legal determinations that govern the monetary system by subordinating nations to the will of a global central bank. We discuss the eventual possibility of losing U.S. sovereignty to a global CBDC system below.

By way of that background, let’s turn to two major issues with respect to how a CBDC will be implemented in the U.S. The first issue is customer access: how will a customer access his money in the form of CBDC? Second, what functions and roles will the intermediary institutions standing between customers and the Fed play? We consider these issues in turn.

4. Authentication: Will CBDC be token-based or account-based?

With cash, the rules are simple: if you have the cash in your hand, you can spend it. As soon as money gets digitized, however, the need for some form of verification before a transaction can take place arises. Generally speaking, one of two things must be verified—the money itself or the account from which the money is coming. Each form of verification comes with upsides and downsides.

The verification of the money itself is known as token-based verification. It is the cash being authenticated, not the user. For CBDCs, token authentication would be based on public key cryptography where the money’s owner holds a private key, which signals possession of the CBDC, either in an account or a digital wallet.

The upside of token authentication, at least from the point of view of many users, is that it would allow for privacy in conducting one’s transactions. However, from the point of view of the monetary authorities, token authentication is an invitation to open the sluice gates for money-laundering and the financing of terrorism. In a BIS paper authored by eight major central banks, including the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan, the authors unequivocally stated:

Full anonymity is not plausible. While anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements are not a core central bank objective and will not be the primary motivation to issue a CBDC, central banks are expected to design CBDCs that conform to these requirements (along with any other regulatory expectations or disclosure laws).55

This brings us to account-based authentication, which is how commercial banking is done by users in the present retail digital monetary system, and which does not allow for anonymous transactions. The only real difference, then, between an account-based CBDC system (at least one in which users do not bank directly with the Fed) and the extant account-based digital retail monetary system would be the currency being transacted—it would be CBDC rather than bank money.

This fact hints at two key points. First, since intermediary institutions in a CBDC system would be transacting in CBDC rather than bank money, there is no reason that non-banks such as PayPal, Amazon, BlackRock, and others could not act as intermediaries.

Second, an account-based CBDC system would offer no real advantage in terms of “inclusion” in that retail users would still need to hold private accounts. Again, “inclusion” appears to be an empty objective trotted out by central bankers solely in an effort to reach the goal of getting a CBDC system in place.

There is also the question of how authentication would occur in a CBDC system. In the current retail system, authentication of checking accounts accessed via debit cards is generally done either by signature or by PIN. Either way, it is the person’s identity being verified. Of course, there is no reason other verification methods would not work. A unique bar code on a person’s skin or a microchip inserted under the skin would work just as well and indeed even better since coding by that route wouldn’t be exposed to the risk of memory loss (PIN) or physical degradation over time (signature).

In any case, it seems all but certain that central bankers will opt for account-based authentication with a new CBDC system.

5. What roles will intermediaries play in a CBDC system?

We believe there are two separate forces faced by intermediaries in a CBDC system that will result in their massive harvesting of personal data from retail CBDC users.

First, a CBDC is a direct and arguably superior substitute (since the Fed is the top dog in the monetary system as explained above) for electronic bank money. For this reason alone, the widespread introduction of a CBDC will suck money out of the retail bank deposit accounts. One commentator put it as follows:

A necessary consequence of any CBDC would be to shift money out of bank deposits and into cash – in this case, digital cash. As a result, those deposits would no longer fund bank loans, which are the primary asset of banks, as well as Treasuries and other assets. Banks’ lending would decrease in supply and increase in cost as banks paid higher rates to persuade businesses and consumers to hold deposits rather than CBDC.56

The loss of bank revenue from loans would only be exacerbated if the Fed were to pay interest on its CBDC. This would force banks to pay higher interest rates themselves or risk an even greater departure of deposit accounts.

In short, when the Fed introduces a CBDC, it is going to put a major squeeze on banks, which will force them to seek other revenue streams. One such stream will likely be personal bank user data: “banks might be forced to harvest and monetize that data in the way that some FinTechs currently do, as they would not be earning net interest income on a CBDC in the way they do with a deposit (and associated loan).”57

Second, central banks are not presently equipped to manage retail payment systems due the massive manpower and complexity scales of the latter with respect to the former. For this reason, central banks will have to outsource management of those payment systems to intermediaries. The disengagement of central banks from the payment process, however, will have the consequence of forcing central banks to rely on meticulous record-keeping at the intermediary level. As the BIS explained:

[A] central bank needs to honor claims that it has no record of. It would thus have to rely on the integrity and availability of records kept by third parties. Consequently, to safeguard cash-like credibility, PSPs [payment service providers] would need close supervision capable to ensure at all times that the wholesale holdings they communicate to the central bank indeed add up to the sum of all retail accounts.58

The same BIS paper notes that when it comes to customer records, the central bank “can maintain record-keeping directly, or outsource it to the private sector and supervise it.”59

Given the public expressions of the importance of privacy concerns in a CBDC system by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, it is a fair bet that the Fed would choose to outsource the collection and maintenance of personal user data to a private concern, likely a large financial company. On this score, we note that the Fed already has a track record of outsourcing some of its functionality—most notably during the pandemic—to BlackRock, the asset management company whose pre-pandemic “Going Direct” plan the Fed adopted.

F. Potential Loss of U.S. Sovereignty

CBDCs put the issue of sovereignty at stake, both on the national and individual levels, which we will consider in turn.

1. National sovereignty at risk

Above we saw that the Fed sits atop the U.S. monetary system in two distinct ways. First, the Fed is the de jure head of the U.S. monetary system by virtue of statutory authority, under which the Fed is the regulator of commercial banks.

Second, we also saw that the Fed is the de facto head of the U.S. monetary system by virtue of the fact that it can issue money (liabilities in the form of reserves) without limit, since no one can require the Fed to redeem those liabilities with anything other than liabilities that the Fed can freely issue.

The commercial banks are not unconstrained this way, as we saw, since a customer can demand either that a commercial bank redeem his account in Federal Reserve notes, or that the bank “transfer” his money to another commercial bank (which requires the bank to transfer reserves to that other bank). Either way, the commercial bank must have sufficient cash or reserves, neither of which can be issued by the bank itself, to meet the customer’s demands or risk being bankrupted.

It is the Fed’s dominance over commercial banks in the de facto sense that must be kept in mind with respect to CBDCs, particularly in view of the dubious claims about the importance of cross-border payments.

As shown above, intermediaries are likely to settle transactions among themselves at the wholesale level because the Fed is ill-equipped to handle the massive task of running a retail payment system. Thus, in one sense, the settlement of transactions in a CBDC system is just like the settlement process under the current monetary system: both occur at the wholesale level.

But in another sense, the settlement process at the wholesale level in a CBDC system would be very different from settlement in the current monetary system. In the current system, settlement is needed because bank money from one bank (Bank A) cannot be freely transferred to another bank (Bank B) because bank money is an IOU. Bank B is not going to take on Bank A’s liabilities as its own anymore than you or I would honor an IOU written by a stranger. Thus, to settle the transfer of money from Bank A’s customer to Bank B’s customer, Bank A must transfer to Bank B reserves in the amount of the bank money transferred: it is because the reserves (an asset) balance out the bank money (a liability) that the transaction balances out and can be effected.

But in a CBDC system, this dynamic no longer obtains, because Intermediary A and Intermediary B are not dealing in their IOUs, they’re dealing in an asset, to wit, a CBDC. Settlement in a CBDC system, even at the wholesale level, involves little more than keeping score, just as settlement at the retail level does. If I owe you $100, and you owe me $40, we settle these transactions by netting out our debts, at which point I pay you $60.

But what happens in the case of “cross-border payments” between users of two different CBDCs? Since CBDCs are liabilities (IOUs) issued by central banks, cross-border CBDC payments are much more like interbank transfers in the current monetary system: just as Bank B isn’t going to freely take on Bank A’s IOU as its own, neither will Central Bank B take on Central Bank A’s IOU as its own—even if that IOU is a CBDC; the name of the currency doesn’t change its nature as a liability.

Thus, it is reasonably foreseeable that innocuous-sounding demands for a global settlement currency “just to ensure the smooth functioning of the global monetary system” will be made in the name of assisting cross-border payments.

Moreover, because domestic payment systems are likely to be handled by large intermediary institutions, it is possible that calls for a global settlement currency will come from that layer of the monetary system—the private layer—and that a new global settlement currency, perhaps a cryptocurrency, will arise out of that layer.

At that point, the central banks would be at risk of losing their de facto dominance, since they would no longer be able to freely issue IOUs (CBDCs) without fear of having to redeem those IOUs in something—a new global currency—that they themselves cannot freely manufacture.

Should that happen, it will be the end of monetary sovereignty for nations, which means the end of national sovereignty, period; full stop. Already we have seen examples of how global “rules” have dictated very specific outcomes in cases that involve matters of only national interest. For example, HSBC admitted to violating federal money-laundering statutes as well as the Bank Secrecy Act—crimes committed inside of the U.S. and that should have automatically resulted in severe criminal penalties under American law. Those penalties never came. Instead, a series of “rules” that ultimately came from the Bank for International Settlements were enforced—to HSBC’s advantage and to the detriment of the American public harmed by HSBC’s crimes.60

The loss of U.S. sovereignty that can be inferred from episodes like HSBC will become much more explicit when CBDCs arrive and a world settlement currency is adopted.

2. Individual sovereignty at risk

Personal sovereignty is at risk as well. The relentless drive for “vaccine passports” is undoubtedly directly connected to the data harnessing that will be a central part of the CBDC intermediary function. Already the head of the BIS has openly expressed his contempt for physical cash because “we don’t know who’s using a $100 bill today,” instead preferring a system where central banks can decline to allow individual CBDC transactions to go forward. Combining the personal data harvesting at the intermediary level together with the central bank lust for “rules” of their own making, one can see the imminent loss of personal sovereignty that’s in store should central bankers go unopposed in their push for CBDCs.

For now, it is a very safe bet that the CBDC rabbit hole we are staring into is far deeper than many CBDC advocates would have you believe—and that we had better be very careful about the choices we are currently in the process of making.

G. What Can I Do?

The inexorable march of central banks toward adopting central bank digital currencies is only the latest in a long series of maneuvers necessitated by the inherent flaws in a debt-based monetary system. In any monetary system where debt is substituted for money, the steady push-pull dance of debt bubbles followed by downturns and even depressions is inevitable.

The source of this fundamental problem (debt-based money), however, also suggests where we should be looking for a solution, namely, to our own history of dealing with problems arising from the debt-based monetary system.

The greatest contraction, or at least the biggest and most sustained contraction,61 was the Great Depression. As we saw above, the Great Depression saw a money contraction of some 30% over the course of four years, from 1929 to 1933. In a very real way, CBDCs represent a contraction in the money supply as well, since digital “money” that can be turned ON and OFF at the whim of central bankers isn’t really money at all—it is store credit that can be applied only to approved goods and services. In this light, to the extent CBDCs are adopted, the money supply is contracting.