Józef Mehoffer. Allegory of Saving (1933). Stained glass window, KOMK Bank, Kraków. Photo: Zygmunt Put/Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“All these pieces of paper are issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver…and indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan’s dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold.” ~ Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo

China is the source of many “firsts” (gunpowder, paper, the compass, etc.), and paper banknotes are also in this category. From the 7th century onward, many Chinese dynasties used promissory notes on paper to allow merchants to trade on long routes without carrying the bulk of heavy coins. The presence of such banknotes along the Silk Road was noticed by that famous one-man link between Asia and Europe—Marco Polo. Thanks to him, the idea of banknotes traveled to 13th-century Italy and then slowly spread to other European countries. “Slowly,” because the earliest European banknotes from Sweden did not come about until 1666.

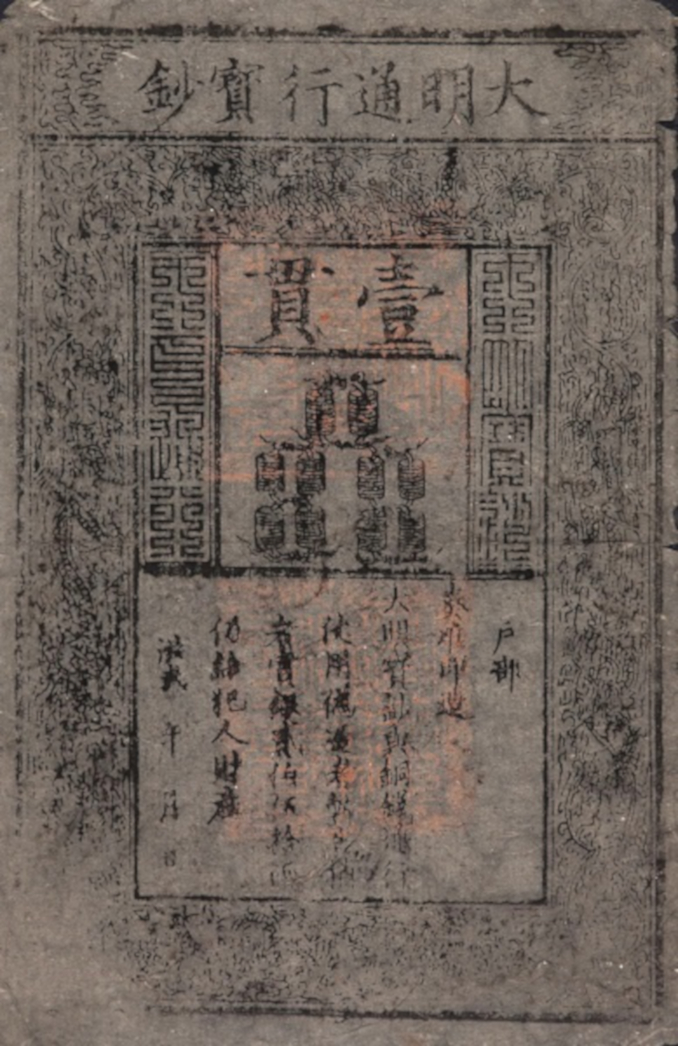

In China, meanwhile, paper or silk banknotes were in use alongside coins, chunks of precious metal, and foreign currency such as silver ingots. A fine example of a Ming-Dynasty-era banknote is displayed at the British Museum. This particular banknote bears its description on the top—Da Ming Tong Xing Bao Chao—which means “Ming Dynasty Circulating Treasure Certificate.” The text below explains the paper’s function and origin as well as issuing a warning that any counterfeiters would be executed.

Ming Dynasty treasury note (circa 1375). The British Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

That was the problem with banknotes from the beginning—once the currency stopped being actual chunks of precious metal, counterfeiting took off. While this early 14th-century Chinese banknote simply carried a warning against fakery, another obvious security measure would have been to create pieces of paper that were hard to fake. And here is where art entered in. The early paper banknotes were just utilitarian but hardly beautiful. This would eventually change in favor of more and more intricate designs, reaching their apogee in the 19th and 20th centuries when both the art of printing and the availability of artistic design became extremely developed.

500-ruble banknote with image of Peter the Great (1912). Russian Empire. Photo: Nina Heyn

Paper currency from Imperial Russia provides a good example of elaborately designed, large-size banknotes that would have had an enormous value were it not for the revolution that nullified fortunes overnight. Before that happened, though, there were some beautiful engravings created for the Imperial banknotes. A 500-ruble banknote featured the mightiest of the Russian tsars, “Peter the Great,” who reigned between 1682 and 1725 and who is credited with transforming feudal Russia into a powerful, modern country. This banknote was the most valuable denomination issued between 1898 and 1917 (the year of the Russian Revolution); during that period, it could be exchanged for 430 grams of pure gold (or could purchase a sizable house). It was also the largest size ever printed in Russia—10 ½ x 5 inches (27 x 13 cm). Peter the Great’s image is based on an 1868 steel engraving of the tsar’s portrait. Many of his official royal portraits feature him wearing steel armor, referencing his military conquests and power.

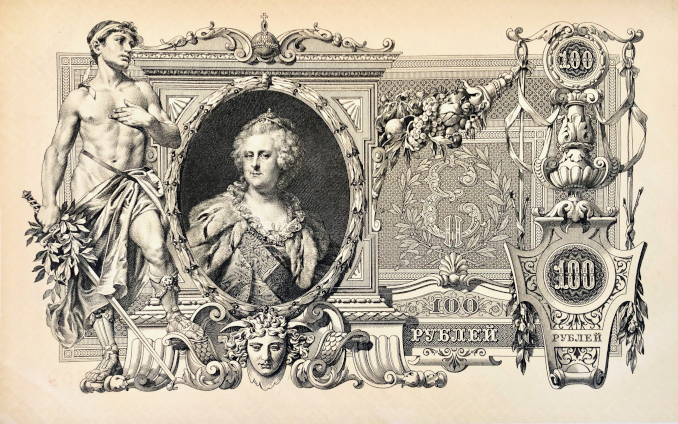

100-ruble banknote with image of Catherine the Great (1910). Russian Empire. Photo: Nina Heyn

The next really mighty Russian ruler was Catherine the Great, a German princess married to Peter the Great’s ineffectual grandson, and one of the few royals at that court who was able to seize power and then maintain it. Her long and fairly peaceful reign is immortalized in another banknote from the end of the Imperial Russian period. A 100-ruble note features her portrait based on a painting by the 18th-century Tyrolean classicist artist Johann Baptist Lampi the Elder. Lampi started out as the royal painter at the court of the last king of Poland. After the Polish king lost his crown—and the country lost its freedom to Russia, Austria, and Germany—Lampi moved to the Russian court of Catherine II and there painted some very flattering portraits of her. Lampi’s portrait of the tsarina to which the engraving refers is now displayed in Poland at one of the royal palaces in Warsaw.

Johann Baptist Lampi the Elder. Portrait of Catherine II of Russia (circa 1791). Łazienki Royal Palace, Warsaw. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In 1925, barely seven years after Poland regained its independence (after 150 years of political non-existence), the Polish National Bank organized a prestigious competition for the design of a new 100-zloty banknote. The conditions were that the front should feature a hero of the Polish freedom fight and a watermark should portray a historical personage. When famous Art Nouveau artist Józef Mehoffer won this competition, he created one of the most beautiful Polish banknotes ever designed.

Józef Mehoffer. Allegory of Prosperity (1933). Stained glass window, KOMK Bank, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Mehoffer was a symbolist and modernist whose paintings, stained glass windows, and polychromic decorations graced many places in central Europe in the early 20th century. For example, commissioned by a savings bank of the city of Kraków, Mehoffer designed in the 1930s elaborate stained glass windows themed as allegories of savings and affluence. These beautiful windows are still inside the historic building.

Józef Mehoffer. Polish 100-zloty banknote (1934). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

For the new banknote, Mehoffer designed the obverse with a portrait of prince Józef Poniatowski (one of the generals in the Napoleonic army fighting for Polish independence) and a watermark featuring the famous Middle Ages monarch Queen Jadwiga—and for the reverse, a painting of an oak tree (symbol of the country’s might and longevity) placed by the seaside (Poland had just regained access to the Baltic sea). It is actually a painting of a specific oak tree that is still growing in a country estate of Wiśniowa in southern Poland. Mehoffer spent a lot of time on this estate whose aristocratic owners were his pupils and who often organized summer plein air gatherings of artists there. The Wiśniowa estate, which hosted most of the prominent Polish painters of the 1930s, used to be called “Barbizon in Wiśniowa,” referring to the famous French artists’ colony.

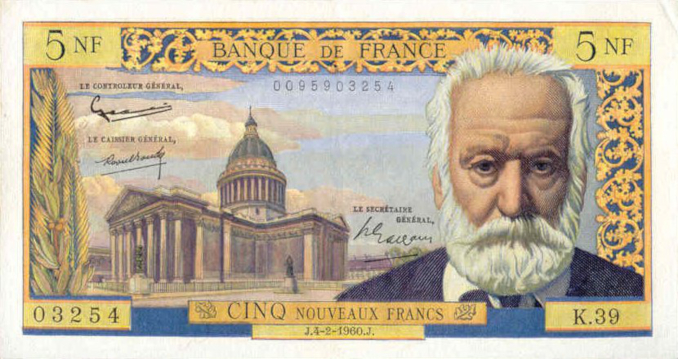

Clément Serveau. 5-franc banknote with Victor Hugo (1960). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The 1930s were also the start of a period when unquestionably the most beautiful French banknotes were designed. Those printed between 1933 and 1958 were created by accomplished artists and were printed in large sizes and many colors. They feature allegorical figures, regional costumes, and portraits of prominent writers, philosophers, and other figures from French history.

Some of these banknotes were designed by the versatile artist Clément Serveau—a muralist who painted in styles ranging from Cubism to Realism, illustrated books with woodcuts, and designed dozens of French stamps. His most outstanding banknote design is a high-denomination note of 10,000 francs that features Napoleon Bonaparte against the view of L’Arc de Triomphe. When the old francs were replaced with new, post-inflationary, lower-denomination francs, the country changed the banknote’s denomination to “new 100 francs” but kept the beautiful design.

Clément Serveau. 10,000-franc banknote with Napoleon (1956). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The model for this engraving was a portrait by the eulogist of the Napoleonic empire, Jacques-Louis David, who started this painting in 1798 but unfortunately never finished it.

Jacques-Louis David. Unfinished portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (1797-98). The Louvre. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

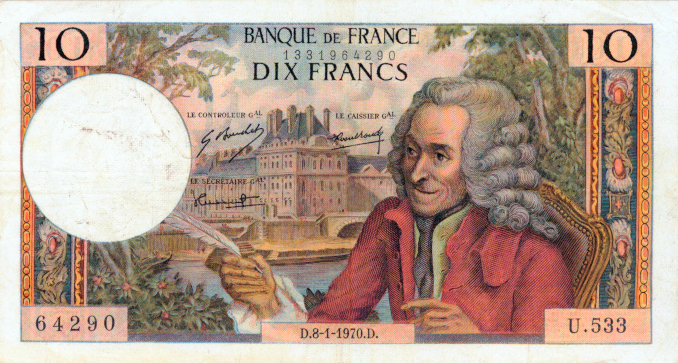

One thing that France has never been short of is painters. So, whenever new banknotes were to be designed, the national bank of France would commission established professional artists to design its notes. A case in point is the often-used banknote of 10 francs. In 1963, that banknote featured the writer Voltaire in a design by French artist Jean Lefeuvre. A watercolor paysagiste (landscape specialist) and an art professor, Lefeuvre designed this banknote as well as equally vivid portraits of Corneille, Richelieu, and King Henry IV.

Jean Lefeuvre. 10-franc banknote with Voltaire (1963). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

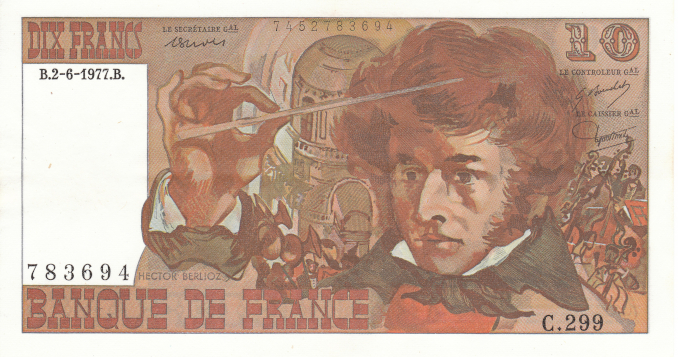

Lefeuvre’s Voltaire banknote was only issued between 1963-1973, thereafter to be replaced with a very romantic (albeit in muddy colors) picture of the composer Hector Berlioz painted by the artist Lucien Fontanarosa.

Lucien Fontanarosa. 10-franc banknote with Hector Berlioz (1972). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Colorful and picturesque banknotes have been less common in Europe since 2002, when the euro replaced local currencies in many countries. On the other side of the world, in Polynesia, the Cook Islands issued a series of colorful banknotes in 1987 with images of daily life, landmarks, and nature. Even there, though, exotic coins and banknotes have given way to more conservative designs. Since 1995, Polynesia’s colorful banknotes have been replaced by New Zealand dollar banknotes that feature more portraits (including the British Queen)—but no more Polynesian ethnography.

50-dollar and other banknotes (1987). Cook Islands. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If there is any moral to derive from the story of old banknotes, it may be that while the banknotes’ monetary value may inevitably disappear with inflation and political changes, the intrinsic beauty of the art the notes display remains for collectors to cherish. Ars longa….